Detect New Files Added to Folder and Upload That File to Server Using Python

A mutual feature in web applications is to let users upload files to the server. The HTTP protocol documents the mechanism for a client to upload a file in RFC 1867, and our favorite spider web framework Flask fully supports information technology, but in that location are many implementation details that fall outside of the formal specification that are unclear for many developers. Things such as where to store uploaded files, how to use them afterwards, or how to protect the server against malicious file uploads generate a lot of confusion and dubiousness.

In this article I'm going to prove you how to implement a robust file upload feature for your Flask server that is compatible with the standard file upload support in your web browser as well every bit the cool JavaScript-based upload widgets:

A Basic File Upload Form

From a high-level perspective, a customer uploading a file is treated the same as any other form data submission. In other words, you take to define an HTML form with a file field in information technology.

Here is a simple HTML page with a class that accepts a file:

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <title>File Upload</championship> </head> <body> <h1>File Upload</h1> <class method="Mail" action="" enctype="multipart/form-data"> <p><input blazon="file" name="file"></p> <p><input type="submit" value="Submit"></p> </class> </body> </html>

As y'all probably know, the method attribute of the <course> chemical element tin be Get or Post. With GET, the information is submitted in the query string of the request URL, while with Mail information technology goes in the request body. When files are existence included in the form, you must employ POST, as it would be impossible to submit file data in the query string.

The enctype aspect in the <class> chemical element is normally non included with forms that don't have files. This attribute defines how the browser should format the data before it is submitted to the server. The HTML specification defines three possible values for information technology:

-

application/x-world wide web-form-urlencoded: This is the default, and the best format for any forms except those that contain file fields. -

multipart/class-data: This format is required when at to the lowest degree one of the fields in the form is a file field. -

text/plain: This format has no applied use, so you should ignore it.

The actual file field is the standard <input> element that we use for most other form fields, with the type set to file. In the instance higher up I oasis't included any additional attributes, only the file field supports two that are sometimes useful:

-

multiplecan be used to let multiple files to be uploaded in a unmarried file field. Instance:

<input blazon="file" name="file" multiple> -

acceptcan be used to filter the allowed file types that can exist selected, either by file extension or by media type. Examples:

<input type="file" name="doc_file" accept=".dr.,.docx"> <input type="file" proper name="image_file" accept="paradigm/*"> Accepting File Submissions with Flask

For regular forms, Flask provides access to submitted grade fields in the request.form lexicon. File fields, however, are included in the request.files dictionary. The request.form and asking.files dictionaries are really "multi-dicts", a specialized dictionary implementation that supports duplicate keys. This is necessary because forms tin can include multiple fields with the same proper noun, as is ofttimes the example with groups of check boxes. This as well happens with file fields that allow multiple files.

Ignoring important aspects such equally validation and security for the moment, the brusque Flask application shown below accepts a file uploaded with the form shown in the previous section, and writes the submitted file to the electric current directory:

from flask import Flask, render_template, request, redirect, url_for app = Flask(__name__) @app.route('/') def index(): return render_template('index.html') @app.road('/', methods=['POST']) def upload_file(): uploaded_file = request.files['file'] if uploaded_file.filename != '': uploaded_file.save(uploaded_file.filename) return redirect(url_for('index')) The upload_file() function is busy with @app.route and then that it is invoked when the browser sends a Postal service request. Note how the aforementioned root URL is split betwixt two view functions, with index() set to accept the Get requests and upload_file() the POST ones.

The uploaded_file variable holds the submitted file object. This is an instance of class FileStorage, which Flask imports from Werkzeug.

The filename aspect in the FileStorage provides the filename submitted past the client. If the user submits the grade without selecting a file in the file field, so the filename is going to be an empty cord, so information technology is important to always check the filename to determine if a file is available or not.

When Flask receives a file submission it does non automatically write it to deejay. This is actually a skillful thing, considering it gives the application the opportunity to review and validate the file submission, as y'all volition see later. The actual file data tin can be accessed from the stream attribute. If the application simply wants to save the file to deejay, then information technology tin can call the save() method, passing the desired path equally an argument. If the file'due south save() method is not called, then the file is discarded.

Want to test file uploads with this application? Make a directory for your application and write the lawmaking above every bit app.py. And so create a templates subdirectory, and write the HTML page from the previous section equally templates/index.html. Create a virtual environment and install Flask on it, then run the application with flask run. Every time you submit a file, the server will write a copy of it in the electric current directory.

Before I move on to the topic of security, I'grand going to discuss a few variations on the lawmaking shown in a higher place that you may find useful. As I mentioned before, the file upload field can be configured to take multiple files. If you use request.files['file'] every bit above you will become only one of the submitted files, but with the getlist() method yous can access all of them in a for-loop:

for uploaded_file in request.files.getlist('file'): if uploaded_file.filename != '': uploaded_file.save(uploaded_file.filename) Many people code their class handling routes in Flask using a single view function for both the GET and POST requests. A version of the example application using a single view function could exist coded as follows:

@app.road('/', methods=['GET', 'POST']) def index(): if asking.method == 'Mail': uploaded_file = request.files['file'] if uploaded_file.filename != '': uploaded_file.salve(uploaded_file.filename) render redirect(url_for('index')) return render_template('index.html') Finally, if you lot utilise the Flask-WTF extension to handle your forms, you can use the FileField object for your file uploads. The form used in the examples you've seen so far can be written using Flask-WTF as follows:

from flask_wtf import FlaskForm from flask_wtf.file import FileField from wtforms import SubmitField class MyForm(FlaskForm): file = FileField('File') submit = SubmitField('Submit') Note that the FileField object comes from the flask_wtf bundle, dissimilar most other field classes, which are imported directly from the wtforms package. Flask-WTF provides two validators for file fields, FileRequired, which performs a cheque like to the empty string check, and FileAllowed, which ensures the file extension is included in an immune extensions listing.

When you use a Flask-WTF form, the data attribute of the file field object points to the FileStorage case, so saving a file to disk works in the same way as in the examples above.

Securing file uploads

The file upload case presented in the previous section is an extremely simplistic implementation that is non very robust. One of the most important rules in web evolution is that data submitted past clients should never be trusted, and for that reason when working with regular forms, an extension such every bit Flask-WTF performs strict validation of all fields before the class is accepted and the data incorporated into the application. For forms that include file fields in that location needs to be validation equally well, considering without file validation the server leaves the door open up to attacks. For example:

- An attacker can upload a file that is so big that the disk space in the server is completely filled, causing the server to malfunction.

- An assaulter tin craft an upload asking that uses a filename such as ../../../.bashrc or like, with the endeavour to play tricks the server into rewriting organization configuration files.

- An attacker can upload files with viruses or other types of malware in a place where the application, for example, expects images.

Limiting the size of uploaded files

To prevent clients from uploading very big files, yous can use a configuration option provided by Flask. The MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH option controls the maximum size a asking body can take. While this isn't an option that is specific to file uploads, setting a maximum request body size effectively makes Flask discard any incoming requests that are larger than the immune amount with a 413 status code.

Let's modify the app.py instance from the previous section to merely take requests that are up to 1MB in size:

app.config['MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH'] = 1024 * 1024 If you endeavour to upload a file that is larger than 1MB, the application will now refuse it.

Validating filenames

We can't really trust that the filenames provided by the customer are valid and safe to utilize, so filenames coming with uploaded files have to be validated.

A very simple validation to perform is to make sure that the file extension is one that the application is willing to accept, which is similar to what the FileAllowed validator does when using Flask-WTF. Let'southward say the application accepts images, then it can configure the list of canonical file extensions:

app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] = ['.jpg', '.png', '.gif'] For every uploaded file, the application can make sure that the file extension is 1 of the allowed ones:

filename = uploaded_file.filename if filename != '': file_ext = os.path.splitext(filename)[1] if file_ext not in current_app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS']: arrest(400) With this logic, any filenames that practise not have ane of the canonical file extensions is going to be responded with a 400 error.

In improver to the file extension, information technology is also important to validate the filename, and any path given with it. If your application does not care about the filename provided by the client, the nigh secure way to handle the upload is to ignore the client provided filename and generate your ain filename instead, that y'all pass to the salvage() method. An case utilize instance where this technique works well is with avatar image uploads. Each user's avatar can be saved with the user id every bit filename, and then the filename provided by the client can be discarded. If your awarding uses Flask-Login, you could implement the following relieve() call:

uploaded_file.save(os.path.bring together('static/avatars', current_user.get_id())) In other cases information technology may be better to preserve the filenames provided by the customer, and then the filename must be sanitized outset. For those cases Werkzeug provides the secure_filename() function. Permit's see how this function works by running a few tests in a Python session:

>>> from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename >>> secure_filename('foo.jpg') 'foo.jpg' >>> secure_filename('/some/path/foo.jpg') 'some_path_foo.jpg' >>> secure_filename('../../../.bashrc') 'bashrc' As you see in the examples, no matter how complicated or malicious the filename is, the secure_filename() function reduces it to a flat filename.

Let's incorporate secure_filename() into the example upload server, and also add together a configuration variable that defines a dedicated location for file uploads. Here is the complete app.py source file with secure filenames:

import bone from flask import Flask, render_template, request, redirect, url_for, abort from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename app = Flask(__name__) app.config['MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH'] = 1024 * 1024 app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] = ['.jpg', '.png', '.gif'] app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'] = 'uploads' @app.route('/') def index(): return render_template('index.html') @app.route('/', methods=['POST']) def upload_files(): uploaded_file = request.files['file'] filename = secure_filename(uploaded_file.filename) if filename != '': file_ext = os.path.splitext(filename)[ane] if file_ext not in app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS']: abort(400) uploaded_file.salvage(os.path.join(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename)) return redirect(url_for('index')) Validating file contents

The third layer of validation that I'one thousand going to hash out is the most circuitous. If your application accepts uploads of a certain file blazon, it should ideally perform some class of content validation and decline any files that are of a different blazon.

How you attain content validation largely depends on the file types your application accepts. For the example application in this commodity I'thou using images, then I tin can use the imghdr package from the Python standard library to validate that the header of the file is, in fact, an paradigm.

Let's write a validate_image() function that performs content validation on images:

import imghdr def validate_image(stream): header = stream.read(512) stream.seek(0) format = imghdr.what(None, header) if not format: render None return '.' + (format if format != 'jpeg' else 'jpg') This role takes a byte stream as an argument. It starts past reading 512 bytes from the stream, so resetting the stream pointer back, because later when the salvage() role is called we want information technology to meet the entire stream. The beginning 512 bytes of the image data are going to exist sufficient to identify the format of the image.

The imghdr.what() office can wait at a file stored on disk if the kickoff statement is the filename, or else it can expect at data stored in memory if the first argument is None and the information is passed in the 2nd statement. The FileStorage object gives usa a stream, so the most convenient selection is to read a safe amount of information from it and pass it every bit a byte sequence in the second argument.

The return value of imghdr.what() is the detected image format. The function supports a variety of formats, amongst them the popular jpeg, png and gif. If non known image format is detected, so the return value is None. If a format is detected, the proper name of the format is returned. The most convenient is to return the format every bit a file extension, considering the application can then ensure that the detected extension matches the file extension, so the validate_image() function converts the detected format into a file extension. This is as uncomplicated equally adding a dot as prefix for all image formats except jpeg, which usually uses the .jpg extension, so this example is treated as an exception.

Here is the complete app.py, with all the features from the previous sections plus content validation:

import imghdr import os from flask import Flask, render_template, request, redirect, url_for, abort from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename app = Flask(__name__) app.config['MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH'] = 1024 * 1024 app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] = ['.jpg', '.png', '.gif'] app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'] = 'uploads' def validate_image(stream): header = stream.read(512) stream.seek(0) format = imghdr.what(None, header) if not format: return None return '.' + (format if format != 'jpeg' else 'jpg') @app.route('/') def index(): return render_template('alphabetize.html') @app.route('/', methods=['Mail']) def upload_files(): uploaded_file = request.files['file'] filename = secure_filename(uploaded_file.filename) if filename != '': file_ext = os.path.splitext(filename)[i] if file_ext not in app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] or \ file_ext != validate_image(uploaded_file.stream): abort(400) uploaded_file.salvage(bone.path.join(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename)) return redirect(url_for('index')) The only change in the view office to incorporate this terminal validation logic is here:

if file_ext not in app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] or \ file_ext != validate_image(uploaded_file.stream): abort(400) This expanded check outset makes sure that the file extension is in the allowed list, then ensures that the detected file extension from looking at the data stream is the same every bit the file extension.

Earlier yous exam this version of the awarding create a directory named uploads (or the path that y'all defined in the UPLOAD_PATH configuration variable, if different) and so that files can be saved there.

Using Uploaded Files

You lot now know how to handle file uploads. For some applications this is all that is needed, equally the files are used for some internal process. But for a large number of applications, in particular those with social features such as avatars, the files that are uploaded by users accept to be integrated with the awarding. Using the example of avatars, once a user uploads their avatar image, any mention of the username requires the uploaded image to appear to the side.

I carve up file uploads into two large groups, depending on whether the files uploaded by users are intended for public use, or they are private to each user. The avatar images discussed several times in this article are clearly in the first group, as these avatars are intended to be publicly shared with other users. On the other side, an application that performs editing operations on uploaded images would probably be in the 2nd grouping, considering you'd want each user to just accept access to their own images.

Consuming public uploads

When images are of a public nature, the easiest way to make the images available for apply by the awarding is to put the upload directory within the application'south static folder. For example, an avatars subdirectory can be created inside static, and and so avatar images can be saved in that location using the user id as proper noun.

Referencing these uploads stored in a subdirectory of the static binder is washed in the aforementioned way as regular static files of the awarding, using the url_for() function. I previously suggested using the user id equally a filename, when saving an uploaded avatar image. This was the mode the images were saved:

uploaded_file.save(os.path.bring together('static/avatars', current_user.get_id())) With this implementation, given a user_id, the URL for the user's avatar can exist generated as follows:

url_for('static', filename='avatars/' + str(user_id)) Alternatively, the uploads tin be saved to a directory outside of the static folder, and and so a new route can be added to serve them. In the instance app.py application file uploads are saved to the location set in the UPLOAD_PATH configuration variable. To serve these files from that location, nosotros can implement the following route:

from flask import send_from_directory @app.route('/uploads/<filename>') def upload(filename): return send_from_directory(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename) One advantage that this solution has over storing uploads within the static folder is that here you can implement additional restrictions before these files are returned, either directly with Python logic inside the trunk of the function, or with decorators. For example, if you want to only provide access to the uploads to logged in users, you lot tin can add Flask-Login's @login_required decorator to this route, or whatsoever other authentication or part checking mechanism that you use for your normal routes.

Let'south use this implementation thought to show uploaded files in our example awarding. Here is a new complete version of app.py:

import imghdr import bone from flask import Flask, render_template, asking, redirect, url_for, abort, \ send_from_directory from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename app = Flask(__name__) app.config['MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH'] = 1024 * 1024 app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] = ['.jpg', '.png', '.gif'] app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'] = 'uploads' def validate_image(stream): header = stream.read(512) # 512 bytes should exist enough for a header check stream.seek(0) # reset stream pointer format = imghdr.what(None, header) if not format: return None return '.' + (format if format != 'jpeg' else 'jpg') @app.route('/') def alphabetize(): files = os.listdir(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH']) return render_template('index.html', files=files) @app.road('/', methods=['POST']) def upload_files(): uploaded_file = request.files['file'] filename = secure_filename(uploaded_file.filename) if filename != '': file_ext = bone.path.splitext(filename)[1] if file_ext non in app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] or \ file_ext != validate_image(uploaded_file.stream): abort(400) uploaded_file.save(os.path.bring together(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename)) return redirect(url_for('index')) @app.route('/uploads/<filename>') def upload(filename): return send_from_directory(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename) In improver to the new upload() function, the alphabetize() view function gets the listing of files in the upload location using os.listdir() and sends it down to the template for rendering. The index.html template updated to show uploads is shown below:

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <title>File Upload</championship> </head> <body> <h1>File Upload</h1> <form method="POST" activity="" enctype="multipart/form-data"> <p><input type="file" name="file"></p> <p><input type="submit" value="Submit"></p> </form> <60 minutes> {% for file in files %} <img src="{{ url_for('upload', filename=file) }}" way="width: 64px"> {% endfor %} </torso> </html> With these changes, every fourth dimension you upload an image, a thumbnail is added at the bottom of the folio:

Consuming private uploads

When users upload private files to the application, additional checks need to be in place to foreclose sharing files from ane user with unauthorized parties. The solution for these cases require variations of the upload() view office shown to a higher place, with additional access checks.

A common requirement is to just share uploaded files with their possessor. A convenient way to store uploads when this requirement is nowadays is to utilize a separate directory for each user. For example, uploads for a given user tin can exist saved to the uploads/<user_id> directory, and then the uploads() office can be modified to merely serve uploads from the user'southward ain upload directory, making information technology incommunicable for one user to see files from another. Below you tin can see a possible implementation of this technique, one time once more bold Flask-Login is used:

@app.route('/uploads/<filename>') @login_required def upload(filename): return send_from_directory(os.path.join( app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], current_user.get_id()), filename) Showing upload progress

Up until at present nosotros have relied on the native file upload widget provided by the web browser to initiate our file uploads. I'm sure nosotros can all agree that this widget is not very appealing. Non merely that, but the lack of an upload progress display makes it unusable for uploads of large files, as the user receives no feedback during the entire upload process. While the scope of this article is to cover the server side, I thought it would be useful to give y'all a few ideas on how to implement a mod JavaScript-based file upload widget that displays upload progress.

The good news is that on the server there aren't any big changes needed, the upload machinery works in the same way regardless of what method you utilize in the browser to initiate the upload. To show you an example implementation I'grand going to replace the HTML form in index.html with one that is uniform with dropzone.js, a popular file upload client.

Here is a new version of templates/index.html that loads the dropzone CSS and JavaScript files from a CDN, and implements an upload form according to the dropzone documentation:

<html> <head> <title>File Upload</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/dropzone/5.vii.1/min/dropzone.min.css"> </head> <body> <h1>File Upload</h1> <form action="{{ url_for('upload_files') }}" class="dropzone"> </course> <script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/dropzone/5.7.ane/min/dropzone.min.js"></script> </trunk> </html> The 1 interesting affair that I've establish when implementing dropzone is that information technology requires the activity attribute in the <form> element to be set, even though normal forms accept an empty activity to point that the submission goes to the aforementioned URL.

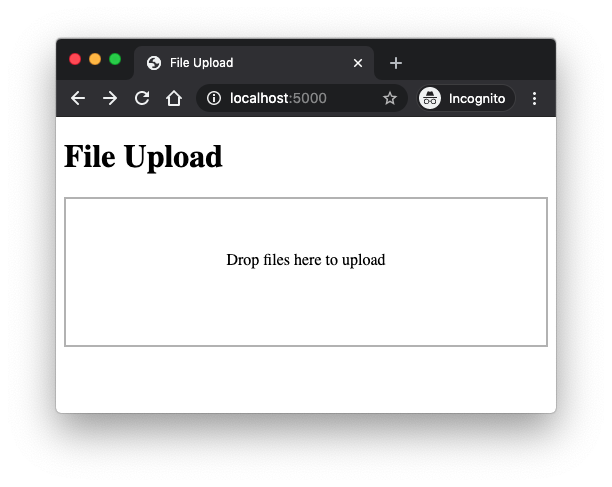

Offset the server with this new version of the template, and this is what you lot'll get:

That's basically it! You lot can now drop files and they'll be uploaded to the server with a progress bar and a terminal indication of success or failure.

If the file upload fails, either due to the file beingness likewise large or invalid, dropzone wants to display an error message. Because our server is currently returning the standard Flask error pages for the 413 and 400 errors, yous volition see some HTML gibberish in the fault popup. To right this we can update the server to return its error responses every bit text.

The 413 error for the file as well large condition is generated past Flask when the request payload is bigger than the size set in the configuration. To override the default error folio nosotros have to use the app.errorhandler decorator:

@app.errorhandler(413) def too_large(e): return "File is too large", 413 The second error condition is generated by the application when any of the validation checks fails. In this case the error was generated with a arrest(400) call. Instead of that the response can exist generated straight:

if file_ext not in app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] or \ file_ext != validate_image(uploaded_file.stream): render "Invalid image", 400 The final alter that I'm going to make isn't actually necessary, but information technology saves a bit of bandwidth. For a successful upload the server returned a redirect() back to the main route. This caused the upload class to be displayed again, and likewise to refresh the list of upload thumbnails at the bottom of the page. None of that is necessary now because the uploads are washed as background requests past dropzone, so we can eliminate that redirect and switch to an empty response with a lawmaking 204.

Here is the complete and updated version of app.py designed to work with dropzone.js:

import imghdr import bone from flask import Flask, render_template, request, redirect, url_for, arrest, \ send_from_directory from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename app = Flask(__name__) app.config['MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH'] = 2 * 1024 * 1024 app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] = ['.jpg', '.png', '.gif'] app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'] = 'uploads' def validate_image(stream): header = stream.read(512) stream.seek(0) format = imghdr.what(None, header) if not format: return None return '.' + (format if format != 'jpeg' else 'jpg') @app.errorhandler(413) def too_large(e): return "File is likewise big", 413 @app.route('/') def index(): files = os.listdir(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH']) return render_template('alphabetize.html', files=files) @app.route('/', methods=['Postal service']) def upload_files(): uploaded_file = request.files['file'] filename = secure_filename(uploaded_file.filename) if filename != '': file_ext = bone.path.splitext(filename)[1] if file_ext not in app.config['UPLOAD_EXTENSIONS'] or \ file_ext != validate_image(uploaded_file.stream): return "Invalid image", 400 uploaded_file.save(bone.path.join(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename)) return '', 204 @app.route('/uploads/<filename>') def upload(filename): return send_from_directory(app.config['UPLOAD_PATH'], filename) Restart the application with this update and at present errors will have a proper message:

The dropzone.js library is very flexible and has many options for customization, and so I encourage you to visit their documentation to learn how to arrange it to your needs. Yous can too expect for other JavaScript file upload libraries, as they all follow the HTTP standard, which means that your Flask server is going to work well with all of them.

Conclusion

This was a long overdue topic for me, I can't believe I have never written anything on file uploads! I'd love you hear what yous remember about this topic, and if you think there are aspects of this characteristic that I haven't covered in this article. Feel gratuitous to let me know below in the comments!

Source: https://blog.miguelgrinberg.com/post/handling-file-uploads-with-flask

0 Response to "Detect New Files Added to Folder and Upload That File to Server Using Python"

Post a Comment